Our work management tools are limiting our imagination

Several weeks ago I had a thought that felt both serious and not serious, so I asked on Mastodon:

Should I write a blog post about companies leaving money on the table by not leveraging their choice of work management tool (Jira, Shortcut, etc) as a competitive advantage?

31% said “yes” and 54% said “a post about what now?”, which I suppose reflects my own feelings about the topic. And it motivated me to write this post - especially that 54%. So let’s talk about work management tools, the original (user) stories, affordances and constraints, and how these tools are limiting our imagination.

What do work management tools do?

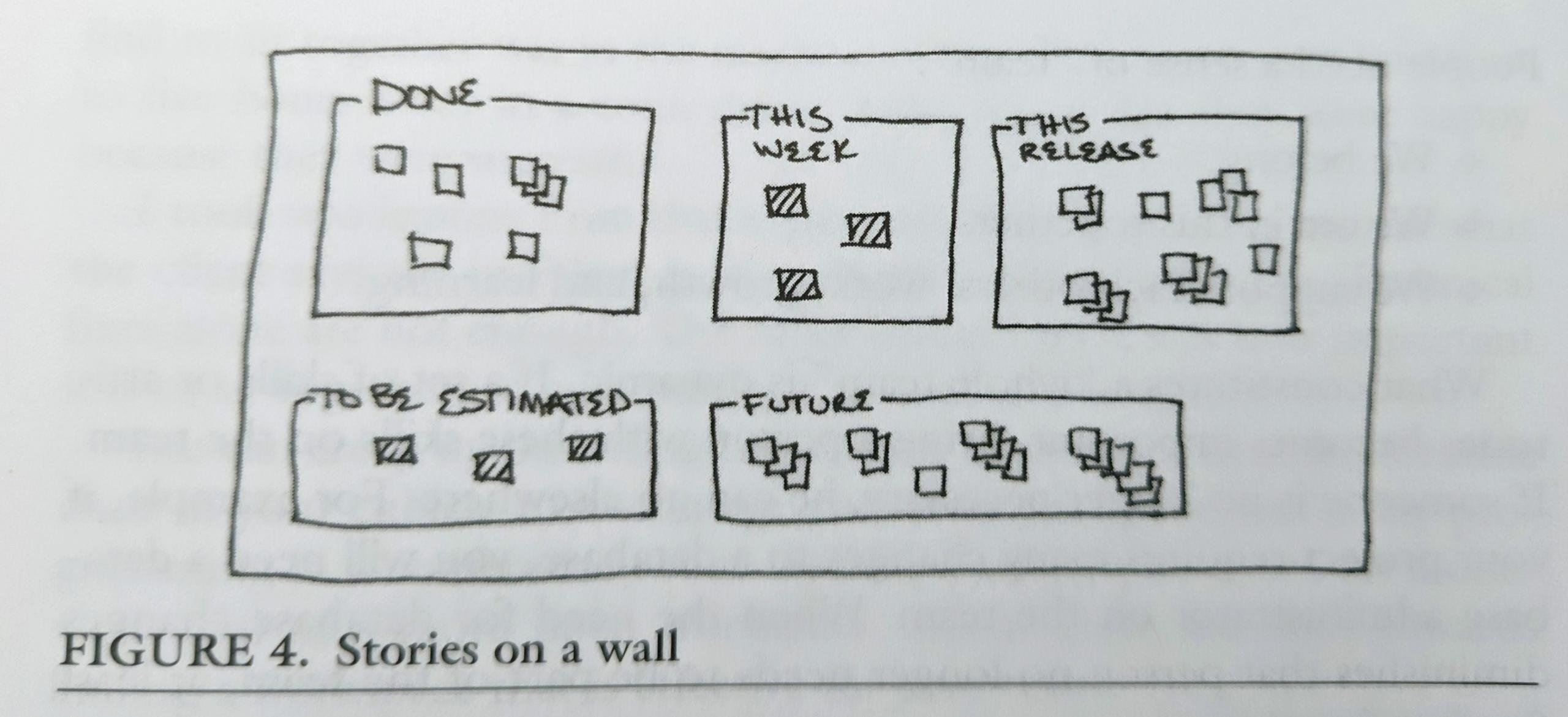

At the core of any work management tool I’ve ever seen or used in software development, are cards representing work, grouped by status. Initially these were physical cards on a wall, as described in “Extreme Programming Explained (2nd ed)” by Kent Beck and Cynthia Andres:

Give stories short names in addition to a short prose or graphical description. Write the stories on index cards and put them on a frequently-passed wall. (p 45)

With the cards sorted by status, it looks like this (p 40):

Note that having physical cards on a physical wall was a conscious choice:

Every attempt I’ve seen to computerize stories has failed to provide a fraction of the value of having real cards on a real wall. If you need to report progress to other parts of the organization in a familiar format, translate the cards into that format periodically. (p 45)

With “Extreme Programming Explained (2nd ed)” being from 2004 this may seem outdated advice, but James Shore delivers the same message in the second edition of “The Art of Agile Development” from 2021:

Finally, another common change is to track stories in a spreadsheet, or issue tracking tool, rather than on index cards. That can make a list of stories easier to read, but it makes visualizations and collaboration more difficult. It’s a net loss that’s hard to appreciate without experience. Give cards at least three months before trying alternatives. Even if your team is remote, use virtual index cards on your virtual whiteboard rather than a spreadsheet or issue tracking tool. (p 138)

And similar to Kent Beck he emphasizes limiting the information on a story or card:

Stories are for planning. They’re the playing pieces of the planning game. That’s it! Alistair Cockburn calls them “promissory notes for future conversations.” (p 13)

Because stories are just a reminder to have a conversation, they don’t need to be detailed. (p 130)

The digitalization of work management tools

However, that didn’t stop almost everyone from switching to computerized work management tools such as Jira, Shortcut, Asana, YouTrack, etc. And these tools allow you to do a lot more than cards on a wall do:

- longer descriptions: requirements or acceptance criteria, implementation details, how to test, questions, risks, etc.

- discuss things in a comments section

- fine-grained statuses with role-based permissions

- additional fields: component(s), issue type, project, priority, fix version, …

- assign stories to one or several team members

- tracking epics and tasks together with the stories

- track relations between cards: relates to, blocks, depends on, …

- integration with your version control and CI/CD pipeline

- graphs (e.g. burn-up/down chart), dashboards, and reports

- maintain a large backlog

- do all of the above across teams

So instead of a lightweight work management tool, we end up with a work administration system. Instead of a tool to enable conversations, we have a knowledge management application. And that leads to problems. I’ll give three examples of problems below and then discuss an underlying bigger problem.

Work management tools used for documentation

With the introduction of description fields, work management tools allow us to capture a lot more detail for each story. So these work items become a form of a documentation. Most of the time a poor form. unfortunately.

They are written before the work is done. Things we learn after refinement are often added in comments (if it all) instead of updated in the description. Work items are transient, you can forget about them once they’re done, while documentation is meant to last. And there is no straightforward mapping between work items and features. The description of one feature might be linked to five work items, some of them amending, changing, or removing parts of other work items. So getting a picture of the current state of a feature based on work items is a form of archeology. Finally, filling the description field of a work item often isn’t sufficient documentation, but since we did write down something, we don’t feel a strong need to create any additional documentation.

Work management tools used for backlogs

Managing a backlog on paper index cards takes some effort, but arguably that’s a good thing. A digital backlog lets you keep adding and adding stuff. There’s no incentive to think twice before adding something, no incentive to clean it up because it’s growing too large. (For some excellent practical advice on this topic, go read Elizabeth Zagroba’s post “Half-Life For Your Backlog”.)

It’s a good thing we have been throwing some proper computing power at our backlogs, or many of us would have ended up as one of Jerry Weinberg’s clients and their bug database:

We have so many bugs, our bug database doesn’t work efficiently. (p 40, Perfect Software and Other Illusions about Testing, Jerry Weinberg)

Work management tools used for work breakdown structures

Breaking down stories into tasks is nothing new. (“Extreme Programming Explained, 2nd ed” describes it on pages 46-47.) Digital tools do make it easier to do that well in advance, because it’s easy enough to update them later. They also make it easy to group stories into epics and let you see all stories in an epic with a click of a button. Then there’s the feature of tracking relations between stories, e.g. dependencies. Finally, we do all of this in one digital tool across all teams. And what we end up with is a reinvention of work breakdown structures, Gantt charts, and PERT charts. The only difference is the agile terminology and hopefully a more vertical way of breaking down work than in the waterfall days.

Managing the work in the work management tool becomes work

With all these additional features and uses of our work management tools, we also spend more time in these tools. Instead of an ancillary tool to facilitate doing the work, managing all the information in the tool becomes actual work. Instead of the tool being an aide for building software, we have to split our time between the software we’re building and the artifacts collected in our work management tools.

Arguably that’s fine. The work needs to be managed, artifacts and tools help us to do so. However, there is the danger of the reifaction of those artifacts. We’re no longer managing the work related to the story, we’re managing the artifacts related to the work for the story. We’re not managing our activities, we’re managing our tickets.

And at the point we’ve strayed quite a bit from the Agile Manifesto‘s “Individuals and interactions over processes and tools” and “Working software over comprehensive documentation”.

Affordances, signifiers, and constraints

With all that said, there’s no getting around this quote:

We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us.1

To delve deeper into the meaning of that observation, we’ll turn to what Donald A. Norman said about affordances, signifiers, and constraints in the revised and expanded edition of “The Design of Everyday Things”.

Affordances and signifiers

Early in the book, Norman provides the following summary of affordances and signifiers:

- Affordances are the possible interactions between people and the environment. Some affordances are perceivable, others are not.

- Perceived affordances often act as signifiers, but they can be ambiguous.

- Signifiers signal things, in particular what actions are possible and how they should be done. Signifiers must be perceivable, else they fail to function. (p 19)

One of the classical examples from his book are doors and door handles. Sometimes you need to push a door to open it, sometimes you need to pull it, sometimes either works. Those are its affordances. But how do you know which of these three it is? That’s where signifiers come in. A sign saying “push” or “pull” is a solution, but a more intuitive solution is to shape the door handle in a way that it’s obvious whether you need to push or pull.

One of my own favorite examples of affordances is comparing Slack with MS Teams. On the one hand, they share a lot of affordances. You can chat with people in channels, to give the most obvious example. On the other hand, they have a very different feel - at least to me. Slack is a place where I can hang out, it’s a social place. Not so with MS Teams, it’s a business and work place.

Constraints

Later in the book, Norman discusses another of the seven fundamental principles of design, constraints:

Constraints. Providing physical, logical, semantic, and cultural constraints guides actions and eases interpretation. (p 73)

Although all four kinds of constraints are relevant here, I want to especially point out cultural constraints:

Cultural constraints and conventions are learned artificial restrictions on behavior that reduce the set of likely actions, in many cases leaving only one or two possibilities. (p 76)

Conventions are actually a form of cultural constraint, usually associated with how people behave. Some conventions determine what activities should be done; others prohibit or discourage actions. But in all cases, they provide those knowledgeable of the culture with powerful constraints of behavior. (p 131)

Affordances and constraints shape our tools and ourselves

Affordances on the one hand, and constraints on the other, map very well to the quote at the start of this section. We shape our tools by adding affordances to them; thereafter they shape us by becoming constraints. And then these constraints might lead us to identify new needs, which become new affordances, and round and round it goes.

Initially these constraints will be mostly on the physical, logical, and semantic level. The tool makes sense in its context. Then with enough adoption, cultural constraints will build around it. The tool will make certain ways to manage work obvious, and others unimaginable. In this sense I think our work management tools have been playing a significant role in the reduction of Agile to the bland flavor of Scrum most Agile teams seem to be using these days.

The constraints of our tools are limiting us

I think there are at least two ways in which these constraints are limiting us. One relates to commoditization and innovation (shoutout to Wardley mapping), the other to ownership.

Most (all?) work management tools are extremely similar, providing the features I listed above. They compete mostly on things like price and legitimacy2, barely on feature sets. They’re a commodity. And through their constraints they also commoditize the way people manage work, i.e. the bland scrum I mentioned above. So no innovation, but also no competitive advantage in how people manage work. Hence me using the words “leaving money on the table” in the question I started this post with.

Of course, it’s very well possible that in your context doing work management like everyone else is perfectly fine. That it doesn’t make sense to be an innovator in this area. However, these constraints are still limiting you. They are limiting the ownership your team members feel when it comes to work management. The tool, not the team, shapes the process.

To give one example, during an Agile Guild meeting at a previous job someone asked: “How do you do story points well?” And despite a colleague and me trying to include the question “What would happen if you stopped using story point?” in the conversation, there was no interest. The person was focused on doing story points and doing them correctly..

Our tools are limiting us in imagining better ways to manage our work.

Let’s reclaim our imagination

At this point it’s important to distinguish two questions. If you say to me “But we still need to do all the stuff these tools allows us to do, right? We need to visualize work, we need documentation, we need cross-team coordination, etc.” I’d reply: “Yes, we do.” But I’d also add the question: “Do we need to do these things in the most obvious way according to our tools?” Because I don’t think we do.

We don’t need to accept the constraints created by our work management tools. And that can start small. Get rid of one of the many fields on your cards and see if anyone misses it. Create a virtual whiteboard for each epic and use that instead of the Description fields. Limit the number of “in progress”-columns (ideally to one), because if your team can’t remember the status of everything you’re working on, you’re probably doing too many things. Stop distinguishing bugs and features in your backlog, because once they’re in the backlog, it matters what value they add to the product, not if they’re a bug or a feature.

And if you’re ready for something larger, Maaret Pyhäjärvi is a great inspiration. She recently shared a list of things she has done differently in the past, and she has published a blog post about how she “got to stop using Jira for planning and tracking of work”. (And yes, her post was definitely an inspiration for this one.)

We need to reclaim our imagination, both in big and small ways. Uncover better ways of developing software by trying out different things.3 And perhaps it won’t ever happen again that 17 people discovering these new ways get together and publish a manifesto that captures the moment and shapes an industry. And that’s ok. That too, shouldn’t limit us in what we dare to imagine.

-

This quote is often ascribed to Marshall McLuhan, but that’s up for debate. ↩

-

As in: no one ever got fired for buying Jira. ↩

-

And sometimes we’ll uncover worse ways. Then we dust ourselves off, learn, and try something else. ↩