Thinking about quality: so what to do?

On 30 January 2021 I participated in the Quality Acceleration Peer Conference organized by Huib Schoots and Joost Voskuil. Participants were Alan Page, Areti Panou, Ash Winter, Bart Knaack, Conor Fitzgerald, Rouke de Jong, Gwen Diagram, George Dinwiddie, Janet Gregory, Joost Voskuil, Joost van Wollingen, Martijn Meijering, Rob Meaney, Vincent Wijnen - with Huib Schoots facilitating the peer conference. The main topics mentioned in the invite were: “How can you sell quality?”, “How can you convince people that quality can accelerate software delivery?”, and “What limitations or barriers do you hit?”

Reflecting during and after our discussions on these topics, I realized there are some interesting things going on about how we talk about quality and how to sell it. Enough interesting things to fill more than one blog post, so this will be a four-part series. And I might expand on some ideas in the series after that.

The first three parts covered rather philosophical topics: choosing your value system, exploring what it means to sell quality, and how management paradigms affect quality. At the end of the third post I brought up the main question for this fourth and last post: so now what? If you expect me to get very concrete and specific in this post, I’m afraid I have to disappoint you. What I will do, is share a way to think about actions that has been helpful to me.

Quality is something emergent

Anne-Marie Charrett says in a blog post titled “Emergent Quality”:

“My hypothesis is that quality is an emergent behaviour. It relies on a whole set of independent systems coming together to create this emergent property. We can never truly know what quality is. It’s constantly changing and morphing into different things. For sure, we can provide examples, but know quality itself? I’m not convinced.”

I think Anne-Marie’s hypothesis is correct. We can have long discussions about what quality is (see my first post in this series), but that’s a different question from how do you get quality? How do you get “a whole set of independent systems coming together”? One way would be to get everyone aligned on the problem, on the desired state, and on how to bridge the gap - as I wrote in the second post of the series. But to be honest, often enough I have trouble getting that alignment with myself, let alone with a group of people. Emergent behavior requires us to engage with complexity, with systems thinking, with wicked problems.

It’s about making decisions despite not having all the answers

With quality being an emergent behavior, any tool or method or approach that simplifies that emergent aspect away will be of limited use. Not of no use, because not everything we deal with is wicked or complex, but plenty of things are - especially as we broaden our perspectives. So taking a consequentialist approach (weighing pros and cons), which relies on your insight into the cause/effect dynamics at play, will get you into trouble. The same applies to reductive management paradigms, such as the aristocracy, machine, and behavioral paradigms I described in the third post of this series. You can definitely make things happen with these approaches - up to a certain point. In my experience they result into a Whac-a-mole situation, where numerous initiatives hide the fact that little actual and sustainable progress is being made.

A related problem is that of “implementing change” or of “implementing agile”. We have analyzed the situation, we have decided on the solution, and now we (dare I say “just”?) have to implement it. It’s a machine paradigm approach: there’s a faulty part in our machine, we need to replace it, and everything will run smoothly. Yet that’s not how people and organizations work. Even if you’d start with the blank slate of a new organization, the people you hire won’t be blank slates. They have a history, they learn, they grow.

That’s not to say that I think that large-scale organizational change is impossible. I do think that few organizations have the willingness to commit to such a change to the degree that’s needed to make it a success.

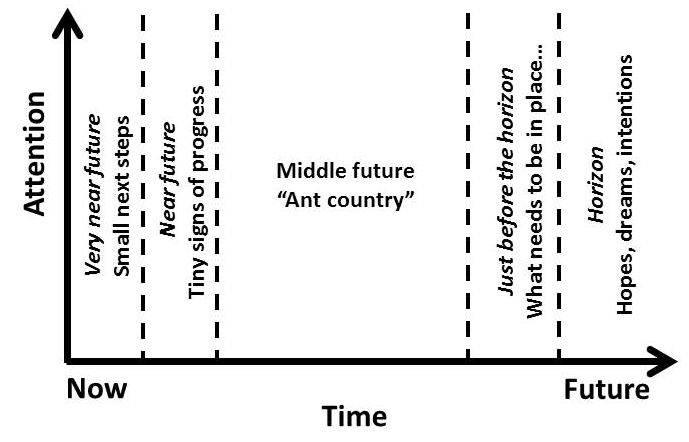

One of the best guides on “how we can be in a complex and emerging world” is the User’s Guide to the Future from the book “Host” by Mark Mckergow and Helen Bailey. It tells us to take small next steps and to look for tiny signs of progress. It encourages us to keep an eye on the horizon, on our hopes, dreams, and intentions, and what would have to be in place for that better future to become real. And finally, it advises us not to worry too much about the middle part, the “ant country”.

This “ant country”, a concept they borrowed from Jack Cohen and Ian Stewart, is too far away to know effectively and thus can’t plan it out effectively. Spending some time on this “middle future” is fine (at some point it will be the “very near future”), but spending too much time is a distraction and can even become a burden. To avoid getting trapped in worrying about “ant country”, McKergow and Bailey advise to embrace dynamic steering: take actions, make adjustments, and keep learning - while using your long-term hopes, dreams and aspirations to give you direction.

If we accept quality as something complex and emergent, then this User’s Guide is a good guide for how we can move towards more quality. In the rest of this blog post, I’ll explore the two aspects of this guide further, i.e. choosing your horizon and taking small steps. As a conclusion I will share how I summarize this approach for myself: managing a network of tensions.

Choosing your horizon

It might be a weird way to phrase it: choosing your horizon, i.e. choosing your hopes, dreams, and intentions. Your horizon probably is something you care deeply about, so it may not feel like a decision, like something you chose. It can also change over time. And a horizon can be a wide variety of things. On a personal level it can be being able to buy a house, moving to a different country, writing and publishing a book, or making it relatively unscathed through a pandemic. On an organization / quality level your horizon could be taking the company public, or raising customer satisfaction scores to excellent, or creating a more humane workplace.

Whatever it is, I think it’s important to be deliberate about your horizon. Giving it thought will allow you to describe it to yourself more clearly. And it will allow you to check your direction: are you still heading towards your horizon? If not, perhaps you need to take some different small next steps, or perhaps it’s time to re-evaluate your horizon. Be careful though not to change horizon so often that you end up not going anywhere. And remember that figuring out a horizon is a perfectly fine horizon by itself.

Another advantage of being deliberate about your horizon is that it allows you to communicate it with others, if you choose to do so. It will help them to understand you and the small next steps you are taking. If you’re familiar with ensembling (also known as mobbing), imagine ensembling without any expression of intent. Everyone but the navigator would be struggling, trying to infer the navigator’s intent from their instructions.

The most important aspect of choosing your horizon is that you own that decision. It’s your horizon and you are responsible for the steps you take towards it. There’s an interesting paradox here: often our horizon is something bigger than ourselves, yet we can’t defer responsibility to that horizon. If we do, it becomes too easy to sacrifice others (even if only in small ways) for the greater good - and we become no better than Lord Farquaad from Shrek: “Some of you may die, but it’s a sacrifice I am willing to make.”

Taking small steps

Two common ways to think about taking small next steps and looking for tiny signs of progress are to consider them as experiments or as the probe-sense-respond of Cynefin’s complex domain. I want to share a third way that has been helpful to me: an analogy to the board game go.

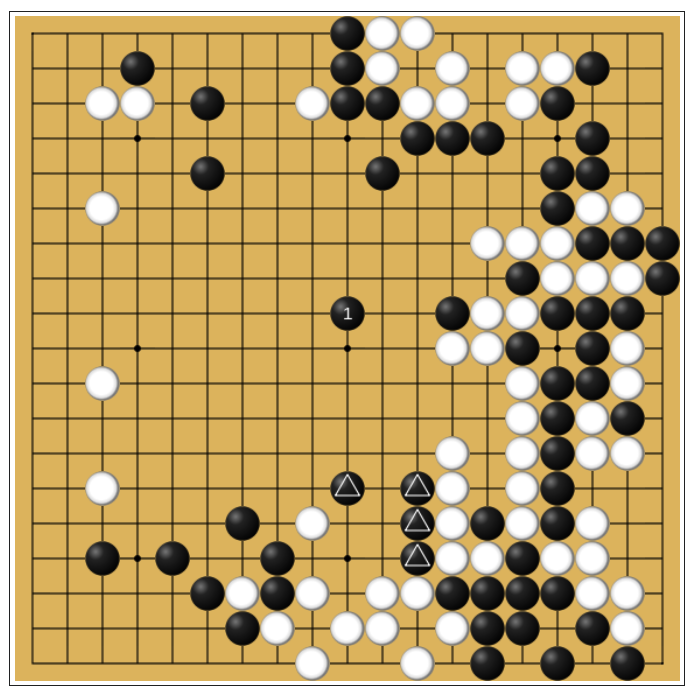

For that, we need to look at the famous ear-reddening move (marked with “1”), played in 1846 by Honinbo Shusaku in a game against Inoue Genan Inseki:

The reason it’s called the ear-reddening move is because after Shusaku played it, a doctor in the audience noticed the ears of his opponent Genan had flushed red, a sign that he had been upset. The strength of this move, as described on Sensei’s Library, is that it has an effect in all four directions. It strengthens the black stones at the top of the board. It reduces the white’s options on the right side. It helps the four black stones at the bottom marked with a triangle. And it sets up a point from which black can expand to the left side of the board. With go being a game about capturing territory, playing a move that strengthens your claim on territory in all four directions, is a great move indeed.

There are several aspects of this move that make it to me a good analogy for taking small steps toward a distant horizon.

First of all, a move in go is a small step. An analysis of about 50.000 professional games showed that the average length of a game was 211 moves. That means each player plays about 100 moves and that a single move is only 1% of a player’s moves in a game. Yet, assuming you play your follow-up moves well, that single move can have a huge impact.

Secondly, this move is a move towards a goal, but not to a well-defined end-state. The purpose of go is to capture more territory than your opponent, which can happen in numerous different ways with very different board configurations. Compare this to chess, where the goal is to capture the other player’s king. This can also happen in numerous different ways, but all of these include the king in checkmate.

Thirdly, the ear-reddening move serves multiple purposes. It has an effect in all four directions and good for Shusaku a positive effect in all those four directions. Since it’s not always (rarely?) possible for a small next step to have positive effects in all areas, it’s good to consider the consequences of a step in several dimensions. For example, in her book “7 Rules for Positive, Productive Change” Esther Derby reminds us when working on change to also consider the negative space through questions such as “What do people have to lose?”

Finally, the move shows how powerful influence can be over a direct confrontation. Tackling something (or someone) head-on will often get you a strong reaction. Pushing leads to push-back. Using a softer approach of influence and oblique strategies allows you to shape the environment to encourage the outcomes you want to happen.

Managing a network of tensions

All these aspects I’ve summarized for myself as: managing a network of tensions. You are a node in a network of tensions and you take small steps to influence those tensions towards configurations that align with your hopes, dreams, and intentions, with your horizon. And that game, that art, those skills, are what I think of when I say “Do something small, and do something today.”